There’s a mass end-of-innocence event going on in the world right now. Everyone is being forced to reckon with not just with the dark side of a corrupt system no dared call out. It’s not that those dark things have never been discussed. Some have spoken or written about them; others have listened and read; still others, have done a little of both. Like me.

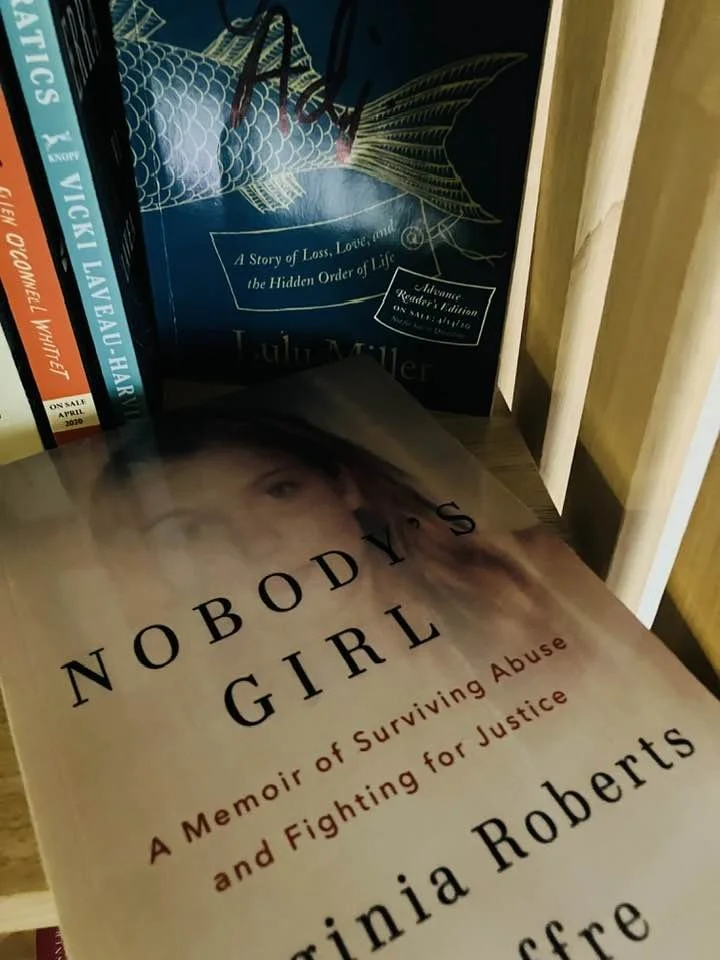

When Virginia Roberts Giuffre’s book, Nobody’s Girl, was published in late October of 2025, I knew I had to read it. I had watched videos of interviews with her and other survivors of the Epstein sex trafficking scandal before then and felt a quiet solidarity with each woman. And especially with Giuffre. Not just because they were women and I was a woman and I knew the dark side of what it meant to live in a female body. But because I had been in situations where I had felt like prey.

Early life shaped her expectations, though she recalls her the years before she turned six with affection. The just after the father she adored presented her with a horse, he began molesting her. The horse became a bargaining chip, one he threatened to take away if Giuffre told anyone about the abuse. Her once loving mother became angry and distant as her husband continued to abuse Giuffre then pass her on to friend who did the same. As a teen she became a runaway who used sex as a way to assert the agency of which she had been stripped.

I understood this. We lived in a beautiful house by the sea where, for a time, my parents tried to live a happily coupled life they inherited from the 1950s. Then they stopped trying to pretend and that was fine; what wasn’t was the war they waged against each other even after divorce, a war that brought out cruelty and violence in one and neglect in the other. I was never molested, though a neighbor boy ironically named Loving once tried to teach me a “game” that earned him a police record. Still, I well understood the feeling of entrapment and survived by making myself small and being grateful for the escape of school.

Without realizing it, Giuffre’s parents had primed their daughter for the exploitation she experienced at the hands of Jeffrey Epstein, whom she later learned had paid her father, the man who had helped her get the job at Mar-a-Lago where she first came into contact with Ghislaine Maxwell, for his silence. She hated servicing him in the way he demanded; but the situation was familiar to her. She had learned a dynamic from early on that transformed her into a victim in the sexual power plays of others whose interest in her was purely instrumental.

My own reckoning didn’t happen in the straight line it did for Giuffre. School became the thing that saved me, the thing that gave me purpose. So while Giufree spent her teen years in and out of reformatories, my life remained stable for as long as I remained within an academic setting. But when that world denied me the permanent place as a professor, my body, then my mind collapsed. At 40 my life spun out of control; stopped making sense. I found another escape in photography and began transforming everything from cityscapes to my own illness-ravaged body into art. One day, I began sharing some of those images on a photo-sharing website, first with the members of a photography class I had been in, then more generally.

What I didn’t realize was something that Giuffre understood only after she became involved with Epstein in Maxwell and “graduated” into becoming not only their on-call sex slave, but also a recruiter for other girls. A “key requirement, other than looks, was [a] vulnerability” that would make them more inclined to the submissiveness they desired in the girls they abused.

The thing that happened to me, that happened half a decade after Giuffre severed ties with Epstein and Maxwell, came of those pictures. Among the many people I interacted with was a man. He used a pseudonym; so did I. Like many, he was complimentary of my photographs. Once or twice, he elegantly crossed the line in what he said but I ignored it. He mentioned in passing he had grown children and sent me a picture of himself that suggested he’d once been attractive. He asked to chat but I said no.

Then losses, betrayals and disasters piled up until one day, teetering on the edge, I said yes. I learned he was a businessman and sometime philanthropist who came from a world where who – rather than what – you knew was power. I knew this because he’d told me once that his well-connected mother had asked a favor from a high-up Canadian government official to list his birth country as Canada even though he’d been born thousands of miles away. A quick online search showed me he wasn’t lying about who he was; still I wondered why a man like him would choose to seek connection on a photo website.

My life entered full freefall a year later and this man offered a small loan. It was a deal with the devil. I became slippery enough that no meeting at the five-star hotels he talked about ever happened. I paid him back when I found my footing again a few years later. But I never forgot the emails, sent every so often, that cajoled. The text messages that, once or twice, turned sexty and which I deleted in disgust. And the rage when, on short notice, I would not drop everything and meet for lunch the one time he came on business in the city where I lived. All for a debt that would have barely paid a month’s rent on a studio apartment.

With this man, it wasn’t about money: it was about using debt to personal advantage and calling it an act of charity. Just as I had between my warring parents, I’d become the uncomfortably comforatble pawn in someone else’s game of control. For Epstein and Maxwell, it was about the thrill of the hunt and knowing that money and promises of opportunity allowed them to lure girls and women, most of them at-risk, into their circle. In both cases it was about using class privilege to control those damaged by circumstance and with no recourse against their will. We never met in person, this man and I; and in the capacity I knew him, he was a pale, lonely shadow of Epstein and Maxwell, but a predator, nonetheless.

Giuffre’s book is more than a #metoo moment. It’s symptomatic of a system made to the measure of those with enough money to make everything, including the law, work in their favor, often at the expense of others. Women know this, have known this, because we are among the groups most subject to exploitation. At the end of Beloved, Toni Morrison’s novel about a black slave woman’s struggle to find healing in post-Civil War America, she writes: “this is not a story to pass on.” Maybe, as more truths emerge about the unjust foundations on which our current system rests, stories of abuse—physical, emotional, sexual—can emerge to break old patterns that should never be passed on.